ASTEROIDS

"I'm going out for the ride — and to take a look at the bones of Lucifer."

— The Rolling Stones, Robert A. Heinlein

Asteroids come in sizes ranging from dwarf planet down to grit. These numbers are for Ceres, the largest.

-

Orbital radius: 2.8 Earth's

-

Diameter: 0.07 Earth's

-

Mass: 0.00015 Earth's

-

Gravity: 0.03 g

-

Year: 4.6 Earth's

Points of Interest:

-

The first asteroid discovered was Ceres, which is natural enough because it is the biggest.

-

Ceres is big enough to be classed as a "dwarf planet," because its gravity is enough to pull it into a sphere.

-

Just like standard planets, some asteroids have moons, lesser asteroids.

-

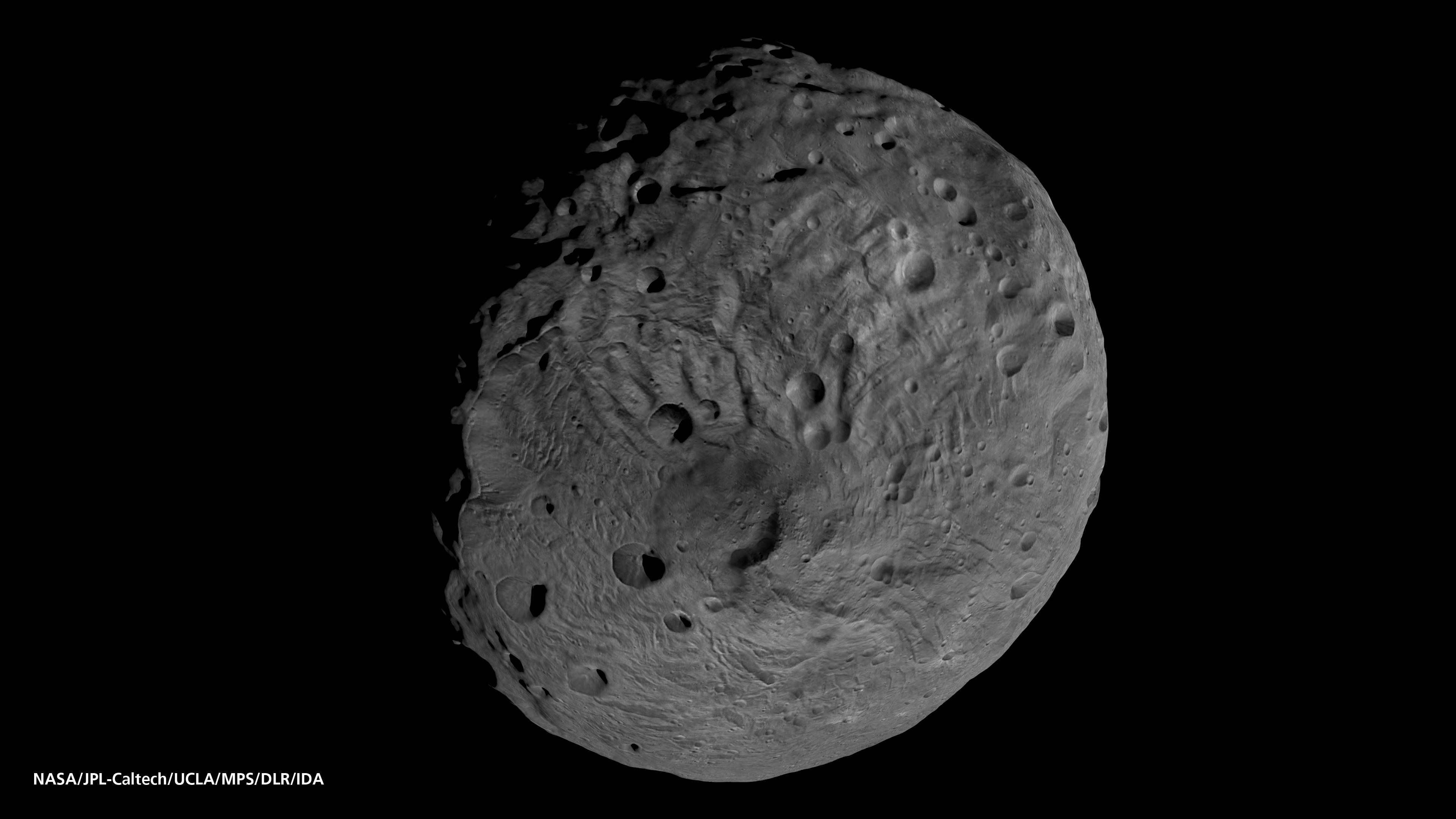

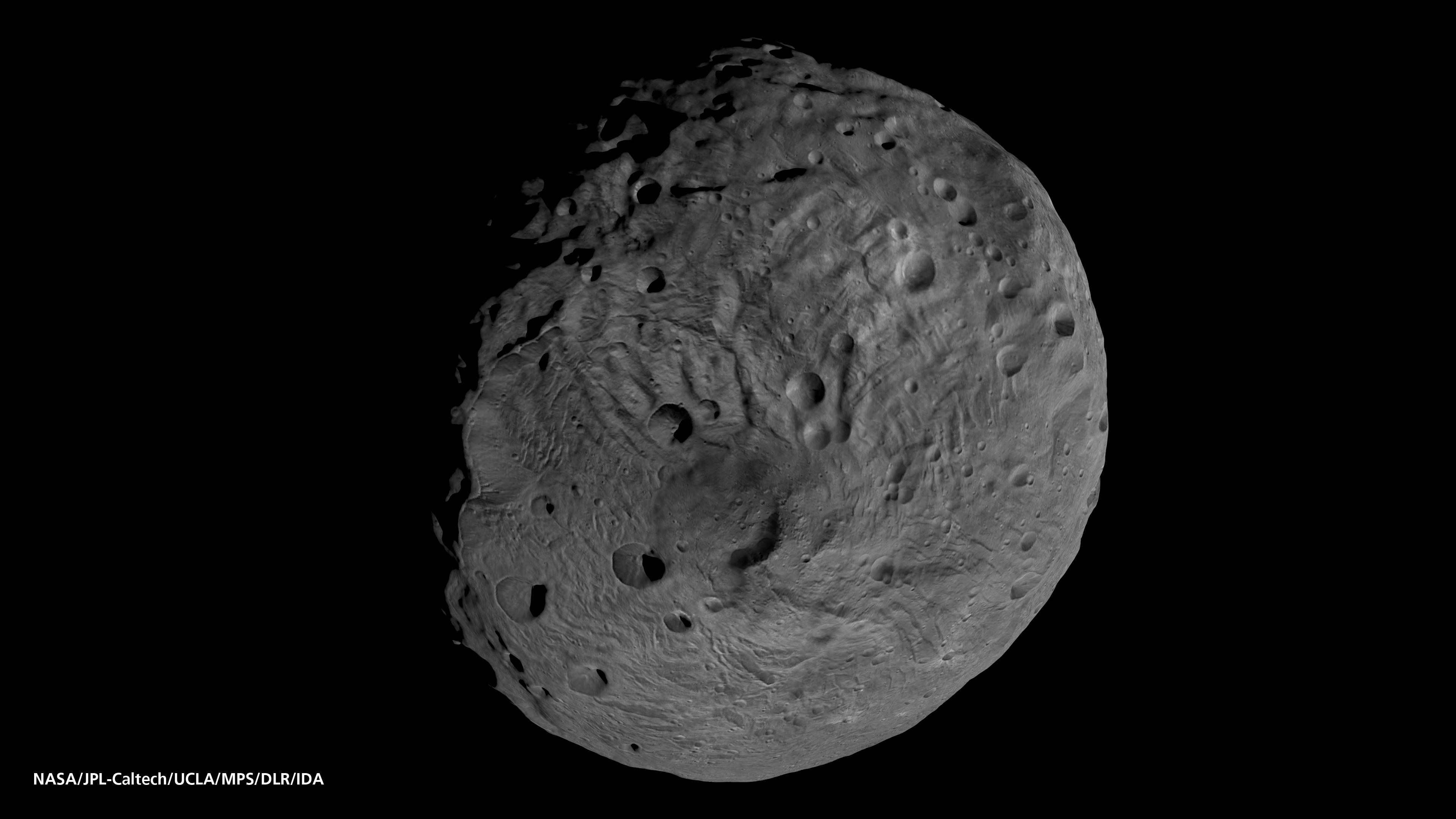

The four biggest asteroids (big enough to have their own (obscure) astronomical symbols) are Ceres, Pallas, Vesta, and Juno.

-

There are vast numbers of asteroids, mostly in the belt between Mars and Jupiter, but the belt is not at all crowded. Probes fly through it as through essentially empty space, unless they are specifically bound for an asteroid.

-

The total mass of all the asteroids is less than that of Mars.

-

Some are mostly iron ore, some are mostly stone, suggesting pieces from the core and crust of a planet.

-

Nonetheless, they do not appear to be the ruins of a lost planet. But they could be the ruins of several small planets that smashed into each other, producing the current batch of asteroids.

-

Meteorites are chips off colliding asteroids and are likewise either iron or stone.

-

Jupiter is the architect of the asteroid belt. Its gravity kept the belt stirred up, preventing the formation of a single planet. For that matter, it may have sent the little proto-planets crashing into each other.

-

The asteroid belt is not one solid ring, but a series of concentric belts. The spaces between the belts are called the "Kirkwood gaps" after Daniel Kirkwood, who discovered them in 1857. They, too, are the work of Jupiter. Any asteroid straying into one of the gaps would have an orbit that would bring it near Jupiter at regular intervals. Jupiter's regular gravitational action would, in turn, move it right back out of the gap again.

-

Besides the asteroids of the belt, there are the Trojan asteroids. They ride the same orbit as Jupiter, 60 degrees ahead and behind that planet, kept in place by gravitational equilibrium between Jupiter and the Sun.

-

Some asteroids aren't in the belt at all, and some of those strays have orbits that cross Earth's. One such crashed into the east coast of Mexico 65 million years ago and ended the age of the dinosaurs. At least, that's where opinion has settled in the last few years.

Asteroids on Earth:

The asteroids were predicted before they were found. Two 18th-century astronomers, Johann Titius and Johann Bode, noticed that the spacing of planetary orbits increases in a somewhat regular fashion and came up with a mathematical formula to express this, the

Titius-Bode law. Only the law predicts a planet between Mars and Jupiter, and there is none. It also predicted a planet beyond Saturn, though, and when Uranus turned up in the predicted orbit, people went back to the space between Mars and Jupiter to see if they had missed anything.

They had. Ceres was discovered on the first day of the 19th century, 1 January 1801, by Giueppe Piazzi. Pallas, Juno, and Vesta were discovered soon thereafter. We are still discovering asteroids, often by computerized scanning. We ran out of god-names a long time ago. Some are named after girlfriends, pets, favorite desserts... Many just get a number. The world registry of asteroids is at the Kirkwood Observatory, at Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana.

Asteroids feature in science fiction chiefly as a place for asteroid miners to work, the science-fictional equivalent of gold prospectors of the Wild West. In somewhat earlier science fiction, asteroids were sometimes the remains of a shattered fifth planet (sometimes named "Phaeton" or "Lucifer"), and the story featured survivors from that planet, or their artifacts, or it was set on the fifth planet during its last days — an astronomical equivalent of drowned Atlantis.

On to Jupiter

Back to Mars

Return to Gallery of Planets

Return to Introduction to Essays

Return to Wind Off the Hilltop

Copyright © Earl Wajenberg, 2012