First Night in Barracks

Rene Wardley (“Renny” to friends and family) lay on the mat in his stall and stared at the clock. 2:00 AM. Exactly nineteen hours before, he had been shot and changed. He had expected to be surprised, confused, bewildered, disoriented. He had hoped to be healthy afterward. All that had come true. He had not expected to be sleepless.

He was in the military now, specifically the cavalry, most particularly the Dedicated Cavalry. Oh, dedicated! Being military, they liked to be exact. He had noticed, in the feverish way you notice things in states of high excitement, that it was exactly 7:00 AM when he and the other five guys had been led out of the locker room, leaving behind the clothes that would never fit again. He had taken three last desperate gasps on his inhaler, then tossed it into the trash. Adrenalin would take him from here.

Outside was the grassy field where they stood naked in the morning sun, in a proper military line. A monster had paced down the line and shot them, one by one, with bow and arrow. Renny had been the first.

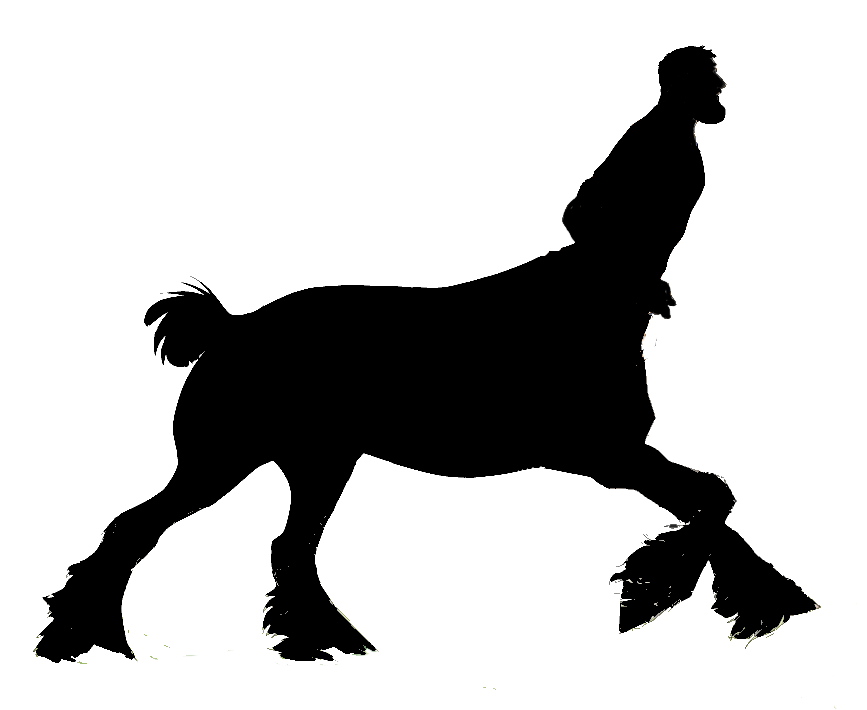

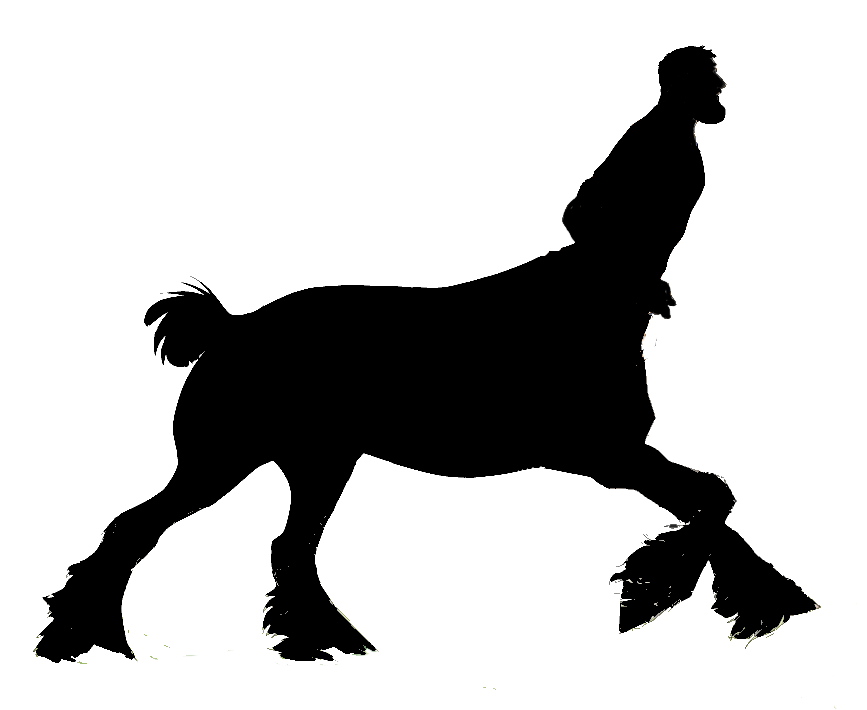

This was all according to plan. The monster was a kind-seeming old gent, half-way at least, the bottom half being a light brown horse. His captain. Captain Philip Fletcher, to be his commander, teacher, and guide, but first to shoot him in the chest. Soldiers had to be brave. Renny had thought about this in terms of the missions he would be sent on. He had not thought about needing bravery to face Fletcher’s dispassionate gaze at the other end of the arrow.

Thump. He fell, not even hurting yet. He remembered the touch of grass, the glare of sunlight, and then he had no time for anything outside his skin.

Not that he could understand what was happening inside his skin. He had no words for the feelings, not then, not now, not ever. “There are no holding places in your mind,” he remembered, either then or later, from some book he had read. He could say he felt he was growing bigger, that he was growing limbs. But what do those things feel like? No words.

No pain either. And no suffocation. That was the first thing he noticed. He took a deep breath. It went on a long time and felt perfect. He let that first perfect breath out with a laugh. Some corner of his mind noticed his laugh sounded different, but that was nothing. He started the second breath, and while it went on and on, he opened his eyes, or maybe just started paying attention to his sight.

An arm lay on the grass. From the angle, it had to be his arm, but it was definitely too thick, might be too long, and was also too pink. Well, when you finally get enough oxygen under your skin...

He lay on his back. And he lay on his side, somewhere. That was confusing. And his waist was uncomfortably twisted. He thought he knew why. How to get up? He pushed himself up on one elbow. But that didn’t get him very far, except to give him a glimpse down a vast, shiny, black something beyond his waist.

Maybe this new body knew how to do it. Just think “Get up,” and not about how.

Thrashing. Flailing black legs in the corner of his vision. Lying on his back in the grass and somehow lying on his back in the grass again.

Okay, think, “Roll over and get up.” On three. One, two, three.

It worked. He was standing. (Twice. Ignore that for now.) But he must have miscalculated, because he was staring down at that palomino fellow with the comic mustache, who was seven feet if he was an inch. Was he accidentally rearing?

He looked down. A chest to match the arms. (Good.) And belly. And the ... next chest, glossy black. And his legs. Forelegs. Not rearing. He was just that tall.

Since he had started the survey, he twisted neck and waist to see what was behind him. No, not behind him: part of him. He had never had occasion to ride a big black draft horse. Now he would spend the rest of his life doing so, in a manner of speaking. How far was it back to his–?

Oh, yeah. He had thought about this beforehand. He tried a couple of things that only produced a swaying of his hips, but at least he could feel that there was something back there. C’mon, wag. Wave. Next moment, he learned how to switch his tail. And that booming noise must be his laughter.

The next couple of minutes he spent picking feet up and putting them down while trying to bend over and watch.

When his attention returned to things other than his own body, he saw the palomino officer gazing (up) at him with amused curiosity from a few feet away. He tried to take his first steps, to say, “Reporting for duty, sir!” or something like that, or maybe just “Thank you!” Let’s see, front left, rear right.

When his attention returned to things other than his own body, he saw the palomino officer gazing (up) at him with amused curiosity from a few feet away. He tried to take his first steps, to say, “Reporting for duty, sir!” or something like that, or maybe just “Thank you!” Let’s see, front left, rear right.

But not at exactly the same time. He teetered over sideways, threw himself the other way, then decided to try for a controlled descent. He got the descent part right. He was now sitting on the grass, his many-seeming legs buckled under him. The doctor sauntered over, clearly not worried—a man of respectable height who now seemed short, a study in contrast with light-weight white jacket and spade-cut black beard. The palomino officer joined him.

“Hurt anything?” the doctor asked.

“No, sir,” Renny answered. His first words with the new lungs. It still sounded like him, mostly.

“Good. Bones like granite, probably. ’Scuse me.” He moved down the line to where a brown-coated creature was also struggling to rise. It had been a teenage boy a few minutes ago, Renny thought.

“Let me give you a hand,” said the palomino. A lieutenant somebody. “Not sure that was much help,” he added, after Renny was back on his feet and once more looking down at him. The lieutenant had been able to provide balance but not much lift compared to Renny’s weight. He held Renny’s hand for a few more seconds, though. “Welcome. And congratulations.” He pumped the hand.

“Thank you, sir,” Renny answered, and found he was grinning for no reason. No, he had plenty of reason. The lieutenant moved on to greet others. The captain was circulating, too. Renny practiced walking and found again that the secret was to not over-think it. Just decide “I’m going over there” and go. Soon, he and the others were wobbling around the field like newborn colts, which was fair enough.

He soon established that he was at least a head taller than the others. But like the others, he kept looking back at himself, incredulous. You shouldn’t see perspective on your own body should you? “I’m a monster!” he exclaimed, laughing.

“We all are, technically,” said the lieutenant, appearing at his elbow. “But monstrous is as monstrous does, I say. You’re getting your feet well. Your families are here. Better say your goodbyes. You’ll see them at Christmas, if we’re still on station here, but not before.”

Renny turned—he had to lumber in an arc to do it—and looked toward the field entrance. There were his parents. He waved, but they continued to peer around. Did they know him? Had his face changed, perhaps? Something cold licked his heart. “Mum! Da!” he called. But he knew his voice was different now.

Not that different. They zeroed in and approached, astonished. He knew that they, like he, had expected him to look something like Don Quixote united with Rocinante, tall (but not this tall), skinny, and ramshackle. They stopped a step away and gaped.

He sat down again. This time the descent was half controlled. It felt right to be shorter than them just now. He almost was. “It worked!” he cried. Boomed. “I can breathe!” They both hugged him, past caring about his nakedness. His mother kissed his cheek. He hugged them both at once, heard them wheeze, and backed off. He had never been strong enough to do that to even one of them.

The next few minutes were a babble of emotion. He tried to express all his gratitude for all the nursing, the endless rapping on the back to help him breathe, the hunts for medications, treatments, therapies, diets, exercise regimes, spells, divinations, finally leading here. They expressed, over and over, often in repeating phrases, their measureless relief. They seemed exhausted with relief. Finally, the three of them just stood (he sat) with arms around each other’s shoulders and wept.

He breathed. Easily. It occurred to him that the three of them had bought this luxury at the cost of his humanity, fourteen years’ sworn service, and whatever risks the expeditionary forces sent him into. But the price seemed fair. A bargain.

During the orgy of relief, he noticed their eyes roving over him, glimmers of astonishment returning. And maybe there were some gleams of horror, but these were lovingly suppressed. He was their kid and he was alive.

The captain came by and gently told his parents it was time to leave. Some more hugs. A few pictures. (His mother even prompted him to strike a strong-man pose.) And they were gone.

He looked around. The other families were trailing out. He had caught glimpses of other meetings during his own:

No one had come to meet the new-minted palomino or the paint. They had talked with each other, the doctor, the officers.

A mother had just parted company with a tan-coated fellow. Renny could see, though her son could not, that she wept through a mask of what was definitely horror.

A big brown job held hands with his parents, all three looking grave to the point of mourning. What could they have been saying to each other?

On the other hand, there was the family of the little red-brown fellow. “Little.” He was shortest of all the transformees, but still the tallest of his family now. Over six feet? Renny’s ability to estimate height was thrown off by the change in his own. This guy was attended by both parents and a sister, all in cavalry uniform—regular cavalry, “Standard Cavalry,” of course, or none of them would have been biped. The parents’ uniforms looked old and distinctly tight, so they were probably retired. All four did get teary from time to time, but none stopped grinning, and father and sister often slapped the new recruit on his shoulder or his flank in an “attaboy” way. Only when they turned to go did the mother let herself bawl.

And then the officers became brisk and the day became busy. They were taken back to the infirmary, through a different, wider, taller door, and measured. They were shown all over the training center and most of the neighboring station for the Standard Cavalry, where the bipedal horse-soldiers had sometimes nodded and waved, more often ignored them. There were the mess, the gym, the track, and the barracks. They went to the stables and met the horses and the brownie. In the barracks, they were issued rusty red T-shirts that were their fatigues, thereby making Renny realize he had spent the whole day naked. Duty jackets and dress jackets would be issued later. Welcome to Life After Pants.

Lectures on routine and discipline. Beginning exercises. Lectures on upcoming classes. Somewhere in the middle was lunch, and later supper, in the mess: innocuous food preceded by huge bowls of dark green sludge called “mulch” that they were ordered to eat. It certainly made the following courses taste better by contrast.

Finally, they were sent to bed. They would be roused bright and early, they were told, so it struck Renny as odd that lights-out was rather late. Actually, no one had said to turn the lights out.

Their quarters were called “barracks,” but each of them had a “stall.” However each stall had a name plate outside the entry, a table, a lamp, shelving for books, and mats to sit or lie on. No straw or sawdust in sight.

Renny noticed a cardboard box on the table. In it were the clothes he had put off that morning, laundered and folded. Under them were his wallet, his phone, his class ring, his crucifix, and an arrow.

It must be The Arrow, he realized, his particular arrow. The shaft was long and wooden. Probably the kind of wood was significant. The feathering was bristly hair. Horse hair? Most likely. And the tip itself was something dark and almost stony. Hoof paring? Did hooves get pared? He would learn.

He pulled open the collar of his T-shirt and looked at the red spot on his chest. He had been told that would soon pale to near invisibility. The magic must be spent, but if he was allowed to keep the arrow as a souvenir, he would do so. Not that he would really need a reminder.

A note in the box told him to take out what he wanted. Anything he left in would be sent back to his home address or to the address he designated. (Fill in the space below.) He left the clothes and removed the rest.

The chain of the crucifix still fit, though the cross now lay near his clavicle, not over his sternum. He kissed it before putting it on. He was Grand Norman: how to use magic with religious propriety was not an issue. He could be grateful for life-saving magic in the same way he was grateful for a new, improved medication. (Only more so.) And he was grateful. He resolved to say so at least once a day forevermore.

He moved out into the corridor, pleased to note he was staggering less. The others were already there or seated in the entries of their stalls.

Now they had the chance to talk to each other and, since no one had really said “lights out,” they did. They started by learning each other’s names and home towns. All were from the English side of Grand Normandy, though scattered about. They talked about places they had been and wondered (1) if they would ever get back to the unSundered ones, considering the obvious, and (2) where they would go as expeditionaries, both fruitless speculations.

The teenage boy (colt?) from the cavalry family was named Daniel Brice and told them the names of their coat patterns. Renny knew “palomino” and “paint” already, and of course he himself was plain “black.” Danny, red-brown, was “chestnut.” The tan fellow with dark hair and tail and legs was a “buckskin.” The biggish guy, brown with darker hair and tail, was a “bay.” And Captain Fletcher was a “dun,” almost a buckskin but with a dark stripe down his back.

The paint was Julien Carlin and gave out nicknames. Renny found he was now “Horsepower,” which was startling and flattering after a lifetime of being feeble and gaunt. The bay, Charles Darneley, was “Charliehorse,” which was inevitable when you thought about it. Darneley seemed resigned to it.

They speculated about the causes of their coat patterns. Carlin seemed puzzled and not very happy about being a paint, but accepted the nickname “Mr. Paint” from Danny equably.

Some of them related their reasons for enlisting. Renny explained about his cystic fibrosis, feeling its absence as a miracle all over again. Danny said his family had been in both cavalries since the start. John Weldon, the buckskin (“Buckjack” but not very pleased with it) just said he wanted to travel. Renny wondered if Weldon could possibly want to travel as much as he himself had wanted to breathe, since each had paid the same price.

Paul Fells, the palomino, movie-star handsome and so far un-nicknamed, offered nothing. Neither did Darneley or “Mr. Paint.”

Surely he should be getting to bed? But he did not feel sleepy. It had, after all, been nothing like an ordinary day. He decided to explore the barracks, which should not take long. He left the others trading tales they had heard about expeditions and found, at the far end, the entry to the showers.

It was floored with concrete, not tile. Between the entry and the showers proper was a row of sinks, set higher than for... for humans (and how strange to no longer class himself there), and a strip of mirrors.

Whoa.

As they had been led around the center, whatever the ostensible topic of the lecture or tour, the real subject of the day had been their new bodies—Walking on four tip-toe legs in 4:4 time instead of heel-toe in 2:2 time. Sitting down with minimum impact. Getting up, or trying to and then trying again. The feel of being so much more massive. Someday, it would surely fade into the background, but today it was front and center.

Renny knew it was that way for the others, too. Whenever they stopped and stood, people (People? Yes, dammit, people.) would lift one leg at a time and flex experimentally, or stare at a hoof, or look over their shoulders at the new second torso (to be called a “barrel“; tomorrow, he would start learning what to call the parts of his own body, in Chenelaise, English, and French). Or (Renny’s favorite) wag their new tails.

But it had all been about feel, all the inside news from the body. There were occasional and disconcerting glimpses of his body, and the new height, but mostly it was feel.

Now he looked in the mirrors and saw himself. No wonder his parents had had a hard time picking him out. His face had not changed, but everything else had. No, even his face had filled out.

A full ton and eight feet tall, the doctor had said at the weigh-in. A glossy black mass with his torso erupting from it. He knew it was his torso, but it didn’t look much like it. He tried the strong-man pose his mother had had him strike. Grotesque. Was she really going to circulate that picture? Had he felt a seam give in the T-shirt?

“Whoa!”

He hastily dropped the pose. It was Danny, the boy from the cavalry family. But he wasn’t looking at Renny; he was looking at his own reflection. His self-absorption made Renny smile. Whatever else they might be, he felt sure they were all still human.

Danny turned and posed, not strong-man style, but trying to get a look at himself from the side. He seemed very pleased with what he saw. He gave a happy little buck and nearly collapsed.

Renny was conscious of some envy. Danny looked like a spirit of spring, even to the youthful awkwardness. He looked back at his own reflection. “I am a monster,” he muttered, then realized he’d said it aloud.

“No, you’re not,” Danny contradicted cheerfully. “You look great!” And it occurred to Renny that the smallest foal in the herd might envy the biggest a bit. In which case, that was a generous contradiction.

He glared at himself in the mirror. The result was a little alarming, but he was thinking, I am not going to let a bit of vanity kill my new happiness. Step back. Look at the big picture. Didn’t you always dream of muscles? They don’t look bad, just unfamiliar. It’s not like you lost any good looks you used to have. “No wait,” he said aloud. “I’ve got this. I was scary before. Do you remember a tall skinny guy this morning?”

“Not really,” Danny admitted.

Renny nodded. They had each concentrated on themselves, naturally.

“That was me. I looked like death warmed over, like the Grim Reaper’s understudy. You learn to not be scary when you look like that. Smile a lot. Be extra polite. Don’t yell unless you really mean it. This is just a different style of scary. I can work around it.”

Danny waved the issue away. “You’re not scary.” Renny raised his eyebrows and loomed just a little in rebuttal. “You could be, if you wanted,” Danny admitted, “but don’t worry. I’ve worked with horses all my life. They’re not scary just ’cause they’re big. The biggest are usually the marshmallows.”

Renny smiled. Smile a lot. “I think I’m having my chain yanked.”

“You mean your reins? Hey, guys, come see yourselves!”

With a clatter of hooves and a chatter of voices, the other four came in. Normally, six horse-sized creatures would crowd a bathroom, but this one was built to cavalry spec, and the barracks had been designed to accommodate up to ten.

He watched their reactions with interest. It was one thing to know, roughly, what you must now look like and another to see it. Only Danny had been simply pleased with his new appearance.

Fells looked worried, though what the palomino could have to worry about when he was flat-out beautiful, Renny could not guess.

Carlin, “Mr. Paint,” seemed sheerly curious, neither pleased nor displeased, but evaluating. He had big ruddy patches on a white ground. It was work to take it all in. He kept turning from side to side, which was hard now that he could no longer pivot on a heel, and once reared slightly with his head turned over his shoulder, to see his equine back in the mirror. “Pretty jazzy,” he said at last, in his sharp, Londonish accent, and seemed satisfied.

Darneley and Weldon registered some worry but more curiosity, and were soon trying out different angles. “I feel like I’m trying on a new hat,” Darneley muttered, his embarrassment plain on his face, but his gaze still fixed in the mirror. “I should ask if it makes my face look fat.”

Danny laughed. “It’s okay. Captain Fletcher said our first job was to get used to ourselves.” He had? Fletcher had said a lot of things today.

Fells looked into the shower stall. It was large enough to be a car wash. “Maybe a hot shower would help me sleep,” he said. “Anyone else?” He took off his T-shirt, paced in, and turned a valve.

“Do they have hot water?” Weldon asked. “I mean, would you use it on a horse?”

They had hot water. Fells’s shower started to steam. He stood under it, eyes closed, apparently trying to lose himself in it.

Carlin laughed. “Sure! Keep clean! Don’t live like animals!” No one else laughed. But, one by one, they doffed shirts and entered. Briefly, Renny remembered other group showers. Exercise was a big part of his life of therapy, which sometimes entailed showers with other boys. Most were polite, or polite-ish, but had still stared at his near-skeletal frame, or had even edged away in case he was catching.

Well, that wouldn’t happen here. Anyway, he’d already spent most of the day walking around naked with these guys. In public. He peeled off the T-shirt (definite faint tearing sounds) and entered.

He didn’t need steamy hot air now, but it had pleasant associations. The water itself, though, was new to him. It pelted all over the new body on stretches of hide he had not possessed this morning, trickling down new legs. The water renewed the strangeness of all these sensations. He felt freshly formed. As he was! It was exhilarating. Fells had the right idea. Renny gave himself up to it.

Some time later, long or short, he was roused by clopping. He opened his eyes and looked around. Fells was still motionless. Weldon was slowly turning about under his shower. Danny and Carlin were doing the same thing, a bit faster. But Darneley was stumbling through tight figure eights, making the clopping. He reached out and turned off his shower.

“That’s enough. Plenty!” he announced, and stumbled out of the showers. His flanks shivered and trembled. That was a normal horse thing, right? Renny couldn’t remember having done it.

“Where are the towels?” he heard Darneley call. He decided that, pleasant as the shower was, he was about as clean and refreshed as he was going to get, so he turned it off and followed Darneley.

Fells did the same. “That’s very focusing,” the palomino said to Renny, “but not relaxing. Not tonight, anyway.”

Renny nodded. “What were you focusing on?”

Fells took a deep breath before answering. “Everything new. All the new stuff.” That was a lot to focus on, and Renny said so. Fells nodded.

Darneley clopped around a corner with an armload of white towels. He passed two to Fells and Renny. “Is this normal?” he asked, looking worried and pointing with a thumb back to his flanks, which still trembled. Just then, the warm air of the showers gave out around Renny and he felt yet another completely new sensation. It was in his left flank. He glanced back and saw it shivering. “I sure hope it’s normal,” he laughed. Fells nodded and said, “It is.”

There followed the longest, strangest toweling Renny or the others had ever been through. Their own rumps, it turned out, were barely in reach, and the best way to reach yours was to crouch down with your horse body hunched and curled like a cat before a mouse hole—not a very equine pose—and reach around first to one side, then the other.

“This,” Renny remarked late in the proceedings, “is the first time I’ve grabbed my own tail.” He toweled it.

“Is that an achievement?” asked Darneley, smiling for the first time since Renny had met him.

“Possibly,” he deadpanned. “A puppy or a kitten couldn’t do it, if it was as new as we are. It’s another new sensation, anyway. That reminds me.” He laid the towel aside and un-crouched half way: that is, with his rear legs still seated, he stood up on his front legs. This position must have a name, he thought, but he didn’t know it yet. “If I’m a baby—and we all are as far as these shapes go—I’m going to play with my toes. Get a good look at them.” And he did. There were, of course, only four toes, one to a foot, but they were big ones.

He lifted his right foreleg and took the hoof in his hands, turning it, prodding, poking. Danny sat next to him and started to do likewise. Darneley laughed, then Fells, then the others, and soon they were all seated on the wet concrete. It turned into an anatomy lesson, with Danny telling them the names of the parts.

“Frog?” Renny exclaimed in mock outrage. “This groove is called a frog?”

“Not the groove,” said Danny, “the sort of triangle the groove is in. The groove is called the cleft.”

“So I have cleft frogs in my feet?”

“We all do.” Danny stared at him, half smiling, making sure he was still kidding. To reassure him, Renny burst into laughter.

Darneley, who had been “playing with his toes” with the rest, asked, “Does anyone else have, uh, kind of double vision about their legs? Double feeling, maybe?” They all stared at him.

“We’ve got double the number of legs, now,” Fells agreed, clearly wondering where this was going.

“I– I mean– Sometimes, when we’re walking around, I just feel like I’m on four legs, and other times, it’s like the front legs are big arms and I’m going on all fours. I mean, all fours the way I did before. Hands and knees. And upright at the same time.” He was wilting under their continued stares. “Do your forelegs feel like arms, for anyone else?” he concluded.

“Not until now,” Weldon said irritably.

Puzzled, Fells asked, “Why do you care how it feels to anyone else?”

“Look!” burst out Carlin, “They’re my front legs and my back legs! They don’t feel ‘like’ anything. They’re just there! Gah! This is like telling someone to notice their tongue!” Renny and Danny laughed, but Renny stopped when he saw Darneley was staring at the cement floor, a flush of embarrassment over face, neck, and upper chest. “I’m going to bed,” Carlin declared. He rose, wobbled a bit, and went back to the stalls at a careful stagger.

“I’d better go, too,” said Fells. “I’ve got to get some sleep!” Weldon followed him out.

Darneley sighed and muttered something. Renny thought he caught, “Even transformed... Still...” The big bay started to struggle to his feet.

“It’s okay,” Renny said quickly. “I know what you mean. Right at the moment, right after I was hit, when I could first make sense of anything– Well, I couldn’t. I mean, I had two backs now and it was like I was somehow lying down twice. And then I was standing up twice, with the four legs.”

“Me, too,” Danny added. “All I could do was thrash around. Did you see me? I tried to push myself up with my arms and used my forelegs instead. Then I tried to get on hands and knees and used my foreleg wrists for knees! The doctor was hovering around, watching me. I wonder what he could have done?”

“Are you afraid you’re going nuts?” Renny asked Darneley. “Because I can’t think of anything more normal than feeling weird right now. This is the weirdest day of our lives!” Darneley stared at him thoughtfully and nodded.

“Listen,” Renny went on, “how good do you feel? Never mind weird. Do you feel good? Comfortable? Healthy?” Darneley’s gaze shifted inward briefly, then he nodded. “’Cause I feel great!” Renny was surprised to find he had sprung to his feet, staggering. “I know! This is the first time I can remember feeling this healthy. Because I’m an expert on what sick feels like. And I’m not! And you’re not!”

Danny clattered to his feet next to him. “Yeah! Don’t worry. This’ll be great!”

By now, Darneley was up. He gave them a tentative smile, thanked them, and made his way to his stall.

Danny watched him go. “You and me,” he remarked to Renny, “are the only ones just plain happy to be here.”

“You are right, pony-boy,” said Renny. “We are so lucky!”

They returned to the stalls. Just before they parted, Danny said, “‘Pony-boy’?”

“Hey, if all four shoes fit...”

Danny chuckled. “Good night, Horsepower.”

But Renny still didn’t feel sleepy. There had been something vaguely like an argument, though he could not say what it had been about, and the stimulation of the shower itself. He turned to his old stand-by, breathing exercises. He arranged himself on his mat like an enormous cat before a hearth, human back upright but relaxed, and simply breathed.

It felt different, of course, and each breath took much longer. But each was also perfectly unimpeded. It felt great.

He reflected on Danny’s words. Happy to be here. It occurred to Renny that he had no problems. He didn’t need help. He could do some helping. True, he was, and forever would remain, an eight-foot one-ton horse-monster, which would have some drawbacks, but it would have advantages, too, such as breathing, being tremendously strong, and breathing. And right now, he had no problems. How many times could anyone say that, any time in their lives?

As the breathing became more automatic, he began hearing the others. There were slight, steady noises from Danny’s stall; maybe he was exercising. There was a tiny, scratchy noise of writing from Weldon’s stall. Most of the noise came from Fells, rolling, shifting, and sometimes sighing in the stall across from his. Fells looked like he still had problems.

Renny weighed a ton. A few hours ago, his two human feet had been replaced with four hooves the size and consistency of bowling balls. The floor was wood. But, by being slow and careful, he was able to get up and cross the aisle without much noise. If anyone had got to sleep, he didn’t want to wake them.

Fells sprawled on the mat, looking very odd. Renny must have looked odd, too, because Fells stared when he saw him. “I’m sorry,” Fells said sotto voce. “Am I keeping you up?”

“No,” Renny answered at the same low volume, “I couldn’t sleep either. Did you want to talk a while before you try again?”

“I don’t want to disturb anybody.”

“We could creep outside. No one said we couldn’t.”

“I don’t think I know how to creep yet,” Fells said, curling up a foreleg and looking at the hoof.

“Yeah, I guess we’re not designed for stealth,” Renny admitted, looking at his own forehooves. He tried to make the mental action that wiggled toes, to see what would happen, but could not remember how.

“Rubber horseshoes,” came Carlin’s voice from the next stall, “and some practice. That’s all you need. And nobody’s asleep. I hear us all moving.”

“Rubber horseshoes?” came Darneley’s voice from across the aisle. Soon, everyone was once again standing in the aisle or sitting in their stall entryway.

“I think we’re all just too stirred up to sleep,” said Weldon. “I mean—” He spread his arms, indicating their altered bodies.

“A sleepless night is no disaster,” Renny told Fells mildly. He had spent many nights up, battling his lungs.

“I just don’t want to be a rag in the morning,” Fells said. “It really gets me down. Way down.”

“Don’t worry,” said Danny. “Horses don’t need much sleep.”

“And that carries over to us?” Fells asked.

“Sure.”

“How do you know?”

“My big brother’s in the cavalry too. Been in for years.”

“Well, well, well,” said Carlin. “We can call you Native Guide.”

“What do you mean?” asked Danny.

“Is anybody else here from an old cavalry family? Or a farm? Or anything horsey?” Heads shook. “You’re the expert. Hell, you’re the only one who knew we had frogs in our feet!” He tapped a forefoot for emphasis.

So only one of us is really into horses? Renny thought. I know why I’m here. Why are the rest of you here?

“But Captain Fletcher and the others know way more than me!” Danny protested. Renny recognized the panic of one who was far more used to being taught than to teaching.

“Yeah, but they aren’t here at one in the morning,” said Carlin.

“All of us know a bit from the inside about what it’s like to be a horse, now,” Renny told Danny, “but you’re the only one who knows about horses from the outside.”

“Well, okay, what do you want to know?”

There was a pause. He had already told them not to worry about their insomnia. “How do we sleep?” asked Weldon. “When we can sleep. I mean, what position do we take?”

“Oh, there are lots. For just dozing, there’s this–” Danny came out into the aisle, wobbled his legs out into a splayed position, folded his arms, then leaned back until his human spine could curve no further.

“–Or you can get down and do that on the floor.” He half-crashed to the floor, gathered his legs under him in the cat-like pose, and leaned back again.

“–Or you could lean against the wall.”

“Ah,” said Weldon. “That’s why there’s a mat on the wall, next to the mat on the floor.”

“Right. Or you can just lie on your side.”

“I guess the only position that’s out is lying on your back.”

Danny laughed and rolled over onto his back. This left all four legs pointing crookedly at the ceiling. “Yeah, that doesn’t work very well any more.” He thudded onto one side, then struggled to his feet again.

Carlin joined in the laughter, but then asked, “So when we’re out in the field, are they going to work us twenty hours a day, or something, because we can do all our sleeping in two?”

“Oh, no,” Danny assured him. “There’s sleep and then there’s rest. I mean, if anybody has a chance to rest, we’ll get our chance too. But there might not be a chance for anyone. Not in the field.” Carlin nodded, satisfied.

“So what do we do now?” asked Fells, and the tone of his voice was different enough that Renny turned to look at him. He was actually smiling a little, looking relieved. Danny’s news about sleep apparently meant a lot to him.

“You heard the expert,” said Carlin. “Rest.” He fetched his phone, then sank again onto his mat and started playing a game. Renny privately considered this a waste of your first night transformed, but maybe Carlin needed to be soothed.

Renny didn’t. He was still just ... rejoicing. He knelt in his entryway and listened to the others chat. For the most part, the chat was Fells, Weldon, and Darneley quizzing Danny about the drills and classes ahead, and Danny answering from the knowledge passed down from his big brother, Ed. Renny reflected that Ed was now big-brothering a whole barracks-full of recruits, by proxy.

A lecture on the virtues of draft horses came to an end. “Hey,” Renny said, “I’m a draft horse, aren’t I? I mean, in my, uh, horse-nature. How much of that applies to me?” A moment later, he realized this was almost fishing for compliments, since Danny had just described draft horses as “patient” and “sweet-tempered,” with “a lot of common sense.” Of course, these must also be the horses he had described as “marshmallows” earlier...

Perhaps fortunately, Darneley took the conversation in a more general direction: “Yeah, they hint in the recruiting literature that there are psychological changes. And the articles I found on transformation said it straight out, at least when it’s the deep kind. ‘Transubstantiation.’ And this is. Do– Do any of you feel like your personality has changed?”

“You are one for twisty questions, aren’t you?” said Weldon, sounding irritated again as he had when Darneley had brought up how they perceived their new legs.

This time, Darneley folded his arms and snapped back, “Occupational hazard. I minored in philosophy.” He looked around at the others. “Well, do you?”

“No,” said Carlin, without looking up from his game.

“I think it’s too soon to tell,” Fells said. “I feel shook up, but I expected to. It’s a natural consequence. I hope–” He broke off.

“Me, too,” said Weldon, with a look at Darneley that might have been an apology. “But actually, I didn’t expect to feel so much like– like me as I do.” He essayed a smile. “Is that philosophical enough?”

Darneley smiled back a bit sadly. “Wherever you go, there you are,” he answered.

“I,” said Renny, “have never been so happy for so long. I don’t know that that’s a personality change. I think it sort of hides any changes there might be. But if I’m now like a draft horse the way Danny describes them, I don’t mind.” He wanted to say to the others, I wish you could be as glad as I am, but he had probably already made them feel awkward. He thought a bit and instead asked Danny, “Did you see changes in Ed?”

“Sure! He had more energy. He was more fun.”

“Was he happier?” Darneley asked.

“Yeah.”

“And was he a happy person before?”

“I guess. Yeah, he always was.”

“So he was still Ed. The same basic personality. Maybe even more Ed than ever before?”

“Yeah, that’s a good way to put it.”

“Well, I hope the results are that fortunate for all of us.” Darneley shot a glance at Carlin. “I have to admit, I’m with Fells: I feel shook up. And on top of that—I’m going to get twisty on you again—I feel so creaturely.”

There was a brief silence. “Well, that’s a word you don’t hear often,” Weldon ventured, but this time without snark. Renny could not recall ever having heard it.

“I mean,” Darneley went on, “I’ve just been reshaped. Remade. We all have. And it brought home to me how I could just as easily be so different from what I am. Even more than this bodily transformation. I mean, suppose Wardley is now patient and wise, and he wasn’t before.”

Renny jerked his head back in surprise at finding himself made an example. “I don’t think–” he began.

“And suppose each of us has had changes that big. It’s a lesson, I guess. We can be changed. We could have been made otherwise. There’s nothing necessary about the way I am. I feel very ... small.”

“That’s a little odd,” said Weldon, “since you’re the biggest one here after Wardley. But I think I know what you’re getting at. Uh, maybe. Is it a philosopher’s job to make people feel uncomfortable?”

Darneley gave him a black-humored grin. “That’s an interesting philosophical question.”

“I shall throw something at you in a minute.”

Renny decided he had just seen the birth of a friendship. “I think I understand, too,” he said. “It’s like I’ve been redefined. Before, I was ‘the guy who can’t breathe.‘ That was my definition, who I was. Not any more. I suppose now I’m ‘that huge creature’!” he laughed.

At the back of his mind, he was considering that little jerk of his head when Darneley had surprised him. It was not a gesture he had used before. He had reared, he realized, like any startled horse. Just a little, but he had. Suddenly, he knew exactly what Darneley meant by feeling creaturely. To some degree or another, his mind and feelings had been re-designed. He had asked for this, but he was not the one who had done it.

Of course, horses don’t rear at a surprising turn in the discussion. He gave himself some humanity points for that.

“Those are just social definitions, though,” said Darneley, bringing Renny back to the said discussion.

“But they rub off on you,” Weldon replied. “Even if you fight them, they’re there in your mind while you fight.”

“And I am ‘that huge creature,’” Renny said. “I don’t mind. It’s way better than being ‘that guy who had trouble breathing until he died of it.‘” He gazed at Darneley, who seemed to poke at ideas as if they were caught in his back teeth. “Are you worried about losing your identity?” And shouldn’t you have thought about that before?

“Oh, no! In fact, I hope–” Then, like Fells, he stopped short. Well, thought Renny, I’ll be rooming with these guys for months. I expect I’ll hear all about it eventually. And we draft horses are patient.

“Is there a problem?” he asked Darneley.

Carlin laid aside his phone. “The problem is he’s a worrier. He worries about how his legs feel, and about his sides twitching, and about his personality, and about being a creature or whatever. What is it with you?” He yawned. “And can it wait until morning?”

Darneley stared at the floor, blank-faced. “Of course,” he said flatly. “I didn’t mean to keep people up.”

Renny felt another equine impulse: to kick Carlin. “You’re not keeping the rest of us up. If Carlin wants to sleep, fine. We can go to someone’s stall and talk quietly there.” Then Danny yawned. In an internal act of blatant favoritism, Renny did not wish to kick him. Instead, he sighed.

“It is getting near two,” Fells noted.

“Not important unless you’re sleepy,” Renny reminded him. “Are you worrying?” he asked Darneley. And what if he was? The only connection Renny had to him was that they had stood in line together to be transformed.

Which, come to think of it, was a strange connection but not an insignificant one. My brothers in transformation, he thought, with an odd kick in the gut. Guts, fore and aft. Oh, my.

Renny had no siblings. After him, his parents had not dared have more.

Darneley made a deliberate effort and made his face come alive again. “No. I am a worrier, but I’m not really worrying now. I just feel overwhelmed.”

“It’s normal to feel weird now,” Renny reminded him. “I feel weird now, too.” He felt excellent. Despite Fells and Darneley worrying, and Carlin and Weldon grousing (though Weldon was better now), and the conversation petering out, Renny still felt as if his veins were bubbling. Nothing as big as I am, he thought, should feel so giddy. A good kind of weird.

Darneley nodded. “You’re right. But it’s wearing me out. I don’t feel sleepy at all. Just exhausted. Every time I move my legs or switch my tail, or when anything touches my– my flanks, I can’t help noticing how different it feels from anything I could have imagined. I– just want a break from feeling weird.”

“That could be a problem,” Fells warned.

“Well,” said Renny, “at least I understand your problem. I think it’s the same for me. Only I enjoy it.”

Darneley gave him a long, thoughtful look. Are you, Renny thought, wondering if all my years of sickness are a fair price for the way I feel now? I wonder too. But that’s not going to stop me from feeling this.

“I know this will all feel normal eventually,” Darneley said. “I just want to be able to think about something else for a bit. Or about nothing.”

“Tell you what,” said Fells, “I have a guitar. If the others don’t mind, I could play. If you just lie quietly and listen, maybe that will take your mind off the way your body feels.”

“Thank you. Even if it doesn’t work, thank you for trying.”

“How about it?” asked Fells. “Is it okay with the rest of you?”

“Sounds good,” said Danny, and yawned again.

“As long as it isn’t flamenco,” Carlin said. He threw up one arm dramatically, snapped fingers, and clattered his hooves at random. “I’d like to see us do that, but not tonight.”

Fells smiled. “I promise. No flamenco.”

Renny grieved a little, to see the conversation break up, but decided a few minutes later that this was foolish. He was back in his stall, doing breathing exercises on his mat, relishing each inhalation. Fells, the guy so concerned to get to sleep, was staying awake to fill the barracks with a slow, wandering, almost tuneless melody. Renny finally felt his excited happiness give way to peaceful happiness. Sleep did not seem impossible, though he still did not feel sleepy. The clock read exactly 2 AM.

Hooves rapped in the aisle. Weldon had been quizzing Danny about something, at low volume, but they were done now and Danny was finally headed to bed. He looked in Renny’s stall. “Good night, Horsepower.”

“Good night, Pony-Boy.”

And the script called for Danny to stumble down the aisle to his own stall. Instead, he blinked at Renny and asked, “What are you doing?”

“Just breathing exercises.”

“Are you doing anything special?”

“Not a lot. You learn to breathe from your diaphragm, is all.” He looked back along his new sides. “I think I have two, now. I’m not sure what the back one is doing.”

Danny nodded, yawned and, apparently without noticing what he was doing, lay down on the mat next to Renny. It was a wide mat, meant for large creatures to sprawl on. If one occupant was tucked up in cat-pose, there was plenty of room.

Danny was already asleep. Renny stared for a moment, then went back to deep breathing. He felt the air stream into his chest, and on into the next chest somewhere. Plenty of air. All the air he could want.

I am so lucky, he thought, or wondered, or prayed. I can breathe. I can breathe! I have a strong, healthy body. And I think I have at least one brother.

Return to Cavalry Cycle

Return to Inkliverse

Return to Wind Off the Hilltop

Copyright © Earl Wajenberg, 2017

When his attention returned to things other than his own body, he saw the palomino officer gazing (up) at him with amused curiosity from a few feet away. He tried to take his first steps, to say, “Reporting for duty, sir!” or something like that, or maybe just “Thank you!” Let’s see, front left, rear right.

When his attention returned to things other than his own body, he saw the palomino officer gazing (up) at him with amused curiosity from a few feet away. He tried to take his first steps, to say, “Reporting for duty, sir!” or something like that, or maybe just “Thank you!” Let’s see, front left, rear right.